Imagine standing in a room with thousands of objects, big and small. You know that you’re going to have to painstakingly sort through them one by one. Not only that, but these objects are often fragile and one-of-a-kind. They represent a community effort that has taken place over the course of nearly 100 years. Hundreds of community members, groups, businesses, and institutions worked together to gather, donate, document, label, store, and preserve these artifacts and the stories behind them.

You also know at some point you’ll be reading through hundreds or even thousands of pages of records, books, interviews, clippings, emails, catalogs, forms, and other documents for many of these artifacts…

A daunting thought, isn’t it?

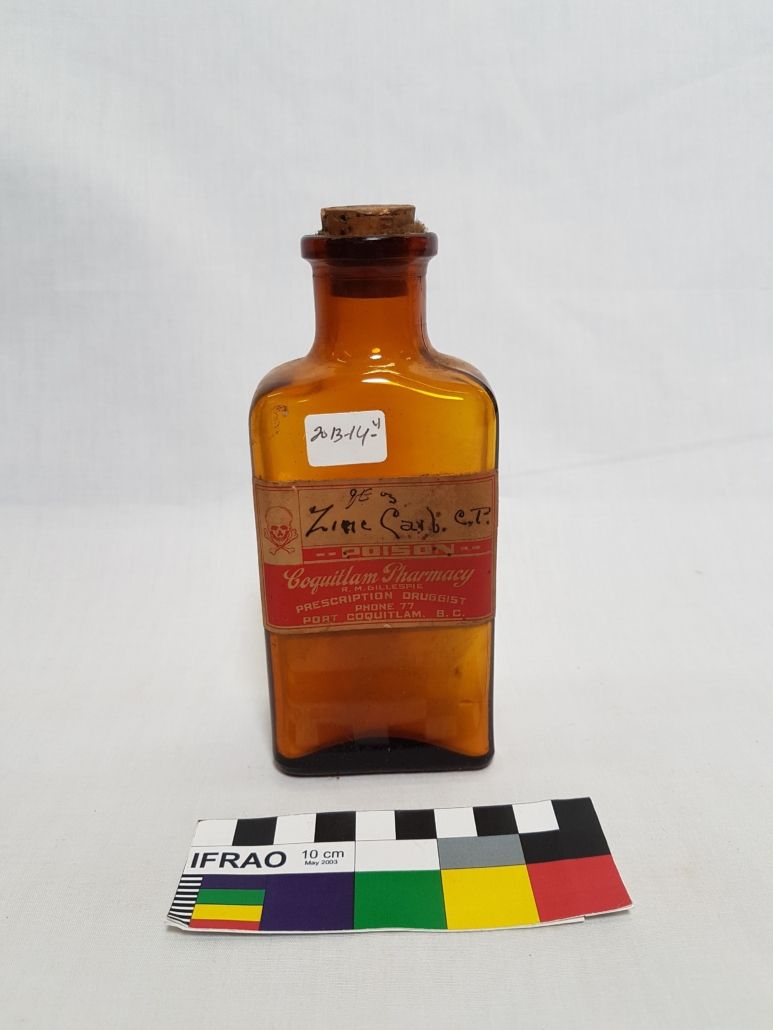

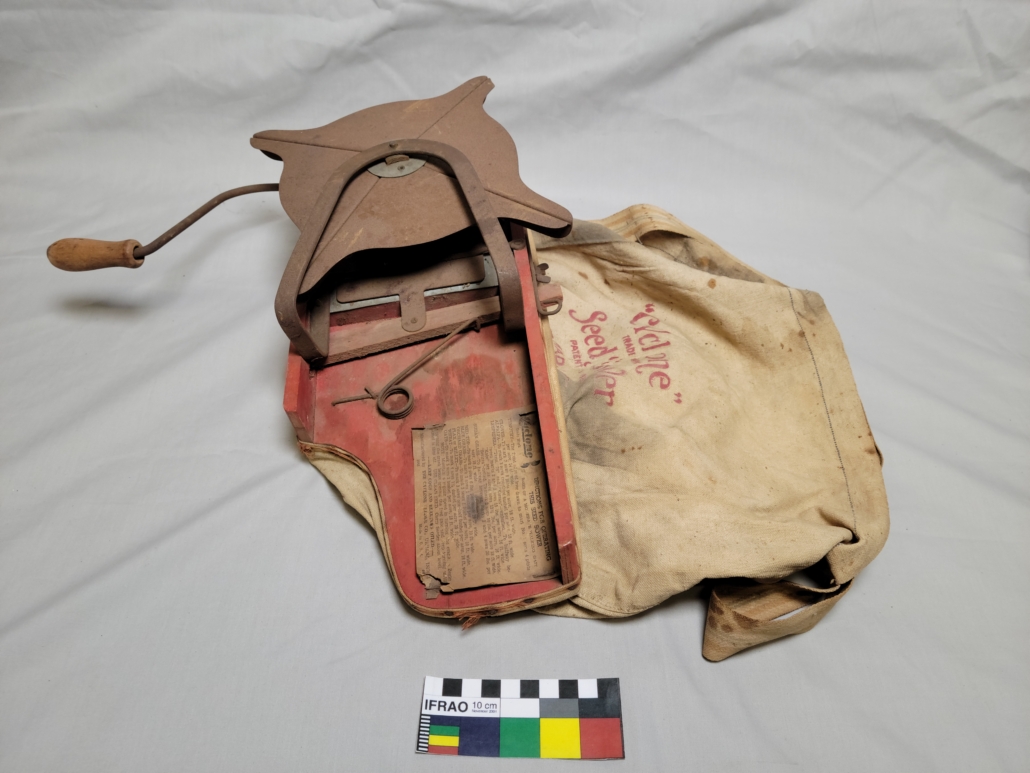

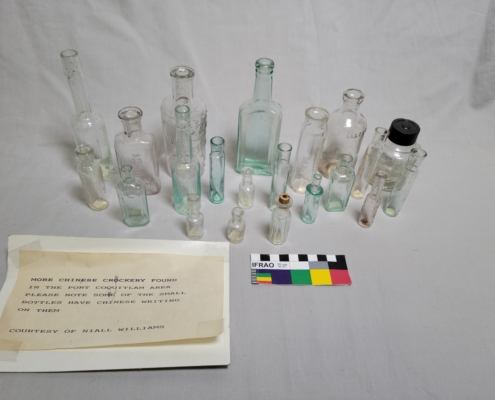

This is where we at the museum found ourselves back not even a year ago when we started a massive project. From sewing machines to crocodile skins, medicine bottles to bombs, we set out to photograph and take stock of each and every artifact.

And photograph we did!

A few of the 2,000+ items we photographed!

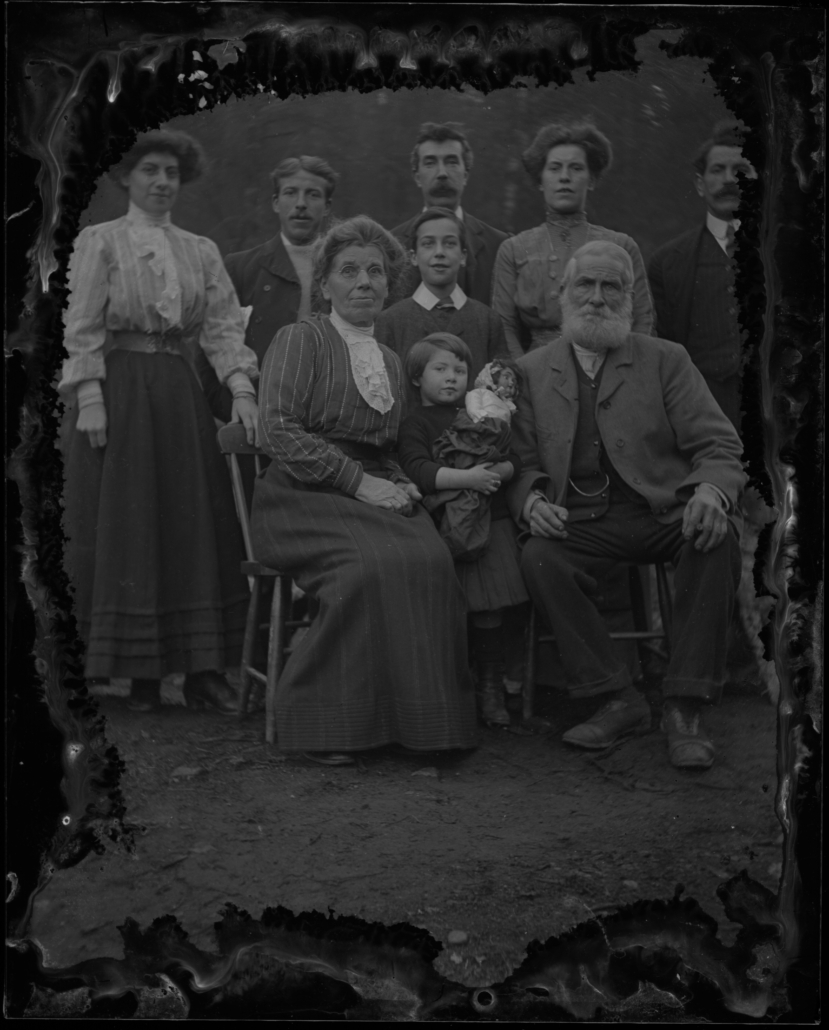

Assistant Curator Mallorie Francis carefully scans one of the Wingrove family photos.

We readied our lights, tripods, backdrops, cameras, and other equipment and then four volunteers and four staff members started work. Shelf by shelf and item by item, they spent hundreds of hours hidden away in the backroom of one of our city’s fire halls and in our archive, carefully going through our collection and records.

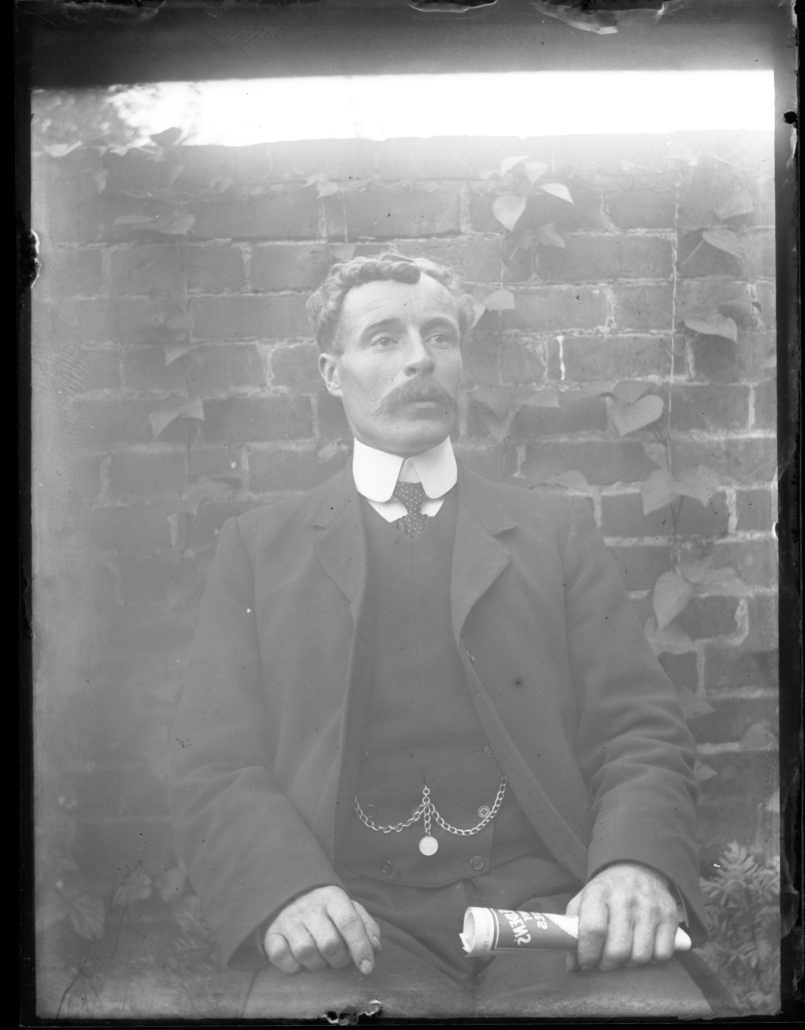

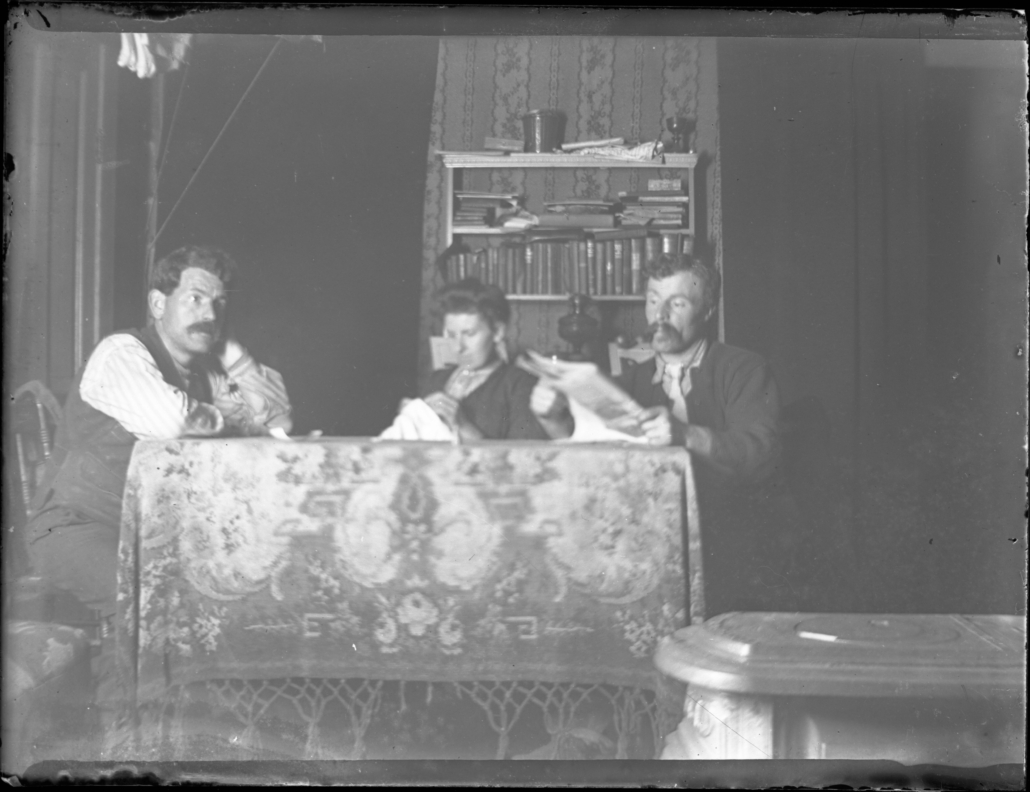

Sometimes what we found called for a different approach. Deep in storage, hiding for many years, was a collection of very old family photographs. Not film, prints, or digital photographs. No, this was an older technology. Glass plate negatives from the 1890s to 1910s!

For each object we looked for labels, recorded measurements, and took down descriptions. We tried to match each object to our old records and add them to our new database. It is painstaking work that isn’t fully complete.

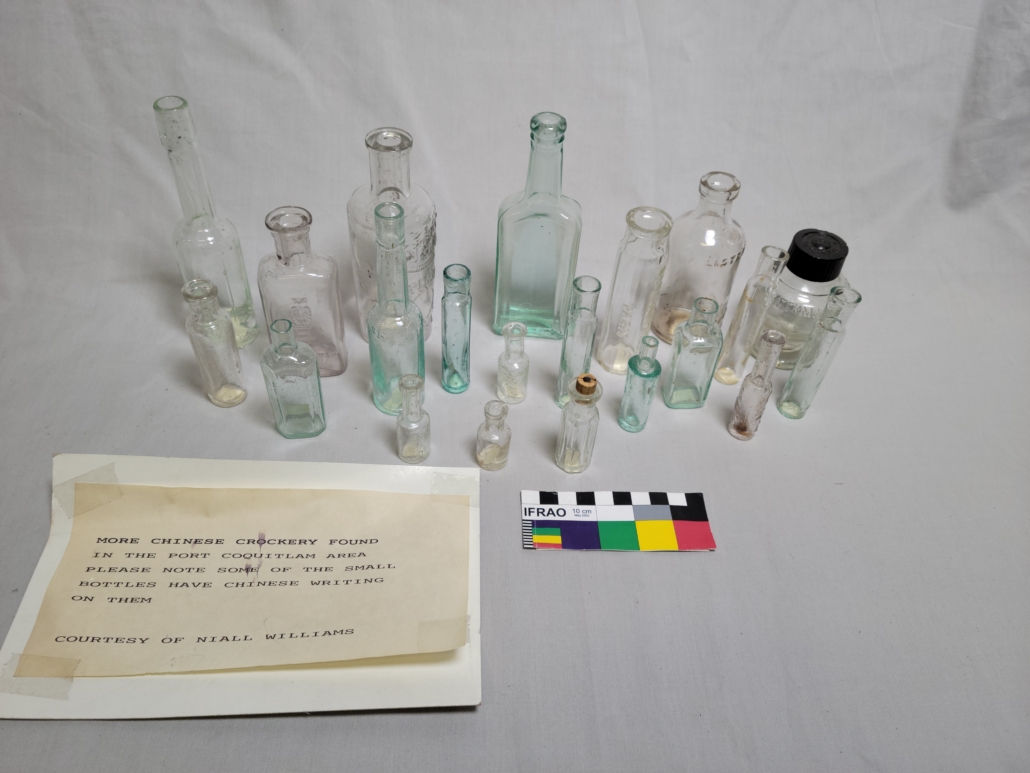

Again hidden away in storage first appeared to be some simple glassware. But, as you’ll come to learn, once the community comes together to uncover the story behind these artifacts, we’ll see that they reveal much more about our history and heritage than you might expect.

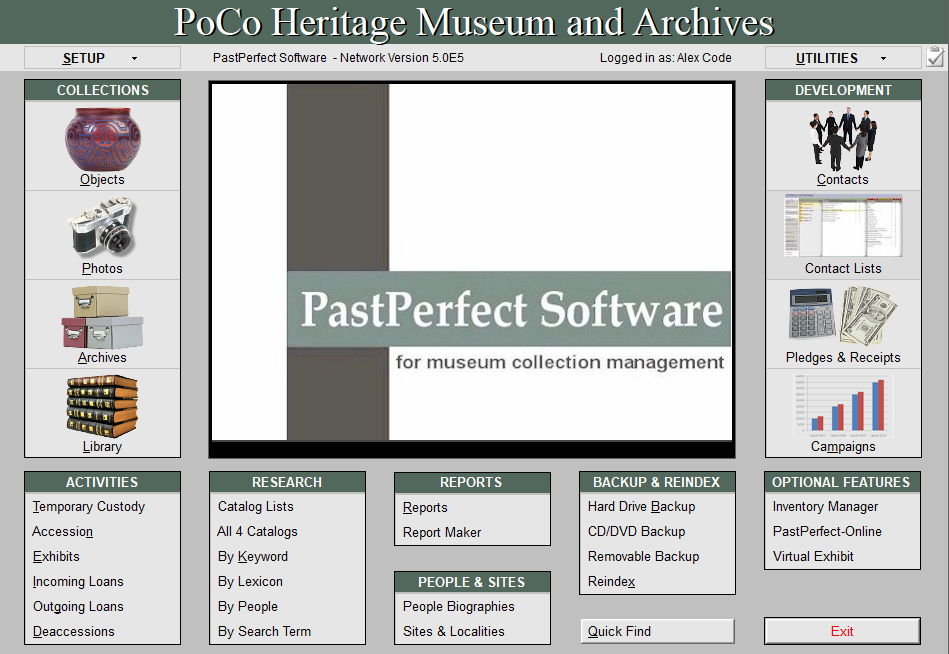

We keep track of our collection with museum database software called “PastPerfect”. Records include donor information, photographs, measurements, descriptions, condition reports, and other details.

Volunteer Queena Li translates a bottle recovered from the Kwong On Wo charcoal burners in Port Coquitlam.

When we start working on a collection of objects, we try to answer the questions of who, what, where, and when. To do this work properly, it requires heritage volunteers, staff, board members, and communities at large work together as a team. In the case of the glassware collection, many of the artifacts had untranslated Chinese inscriptions. So one of the first steps in understanding who these bottles may have belonged to, what they were used for, and when and where they may have come from, was to transcribe and translate the Chinese characters.

One of our collections volunteers, Queena Li, took the lead and got down to work. She found that one of the first objects was a jar inscribed with the Chinese characters 生源腐乳 – which translates to “Sang Yuen Fermented Tofu”. So, with this translation and some further research into the company itself, we’re able to get an idea of what was in the jar and who produced its contents.

Translation of the remaining text revealed the characters 正埠, which literally translates to “Straight Port” in English.

What could “Straight Port” be referring to?

A glass jar embossed with the Chinese characters for “Sang Yuen Fermented Tofu”.

Like this bottle, much of the glassware in our collection is very small.

At this point it becomes clear that it isn’t only the literal meaning of the text that’s important. To really understand any text you have to also be aware of the history and the cultural context.

So, with a little digging into the archives and a collaborative effort between Queena, Lily Liu, Aynsley Wong (all volunteers at PoCo Heritage), and some help from members and elders at the Wongs’ Benevolent Association in Vancouver, they learned that ‘Straight Port’ has several meanings, but it most likely is referring to Vancouver on these bottles!

Also, since we were able to determine that this collection of glassware roughly dates from the 1900s to the 1920s through interviews in the archive, we can say with confidence that 正埠 (Straight Port) was a common word for Vancouver at the time. 正埠 (Straight Port) could also mean New Westminster in older texts though.

So, through translation with a team of volunteers and community members with the needed historical and cultural knowledge, we were able to answer the who, what, where, and when questions for the fermented tofu jar.

Another interesting case in the translation process was a small vial that Queena initially transcribed as 淆衆水 – literally “Confused Congregation Water”. With some hesitancy to the real meaning and now with further questions, volunteer Lily Liu was able to shed some light on the matter. She noted:

I think 淆衆水 (濟眾水) might be used to heal heat stroke (中暑). It’s effective but it tastes bad. I used another Chinese medicine called 藿香正气水 to heal heat stroke when I lived in China. Some medications (liquids and pills) used to heal heat stroke have strong tastes but might work within a couple to several hours when they are used correctly.

Again we can see that cultural knowledge is just as important as linguistic knowledge when interpreting an object. You can see that to properly do the work necessary for documenting, understanding, and sharing our heritage, it requires the efforts of many individuals, groups, and communities. It requires the inclusion of those with the linguistic, cultural, and historic knowledge and should be done respectfully.

Often in the past, however, diverse voices were left out of heritage. This became especially apparent as we began researching the historical background of these objects.

We collect reference materials on people, organizations, places, and events throughout PoCo’s history in our many stand-up files.

Research can take many different forms and includes the work of many different people. From interviews to microfilm, books to catalog records, forms to receipts, the work of piecing together the story and context of an object can sometimes be difficult.

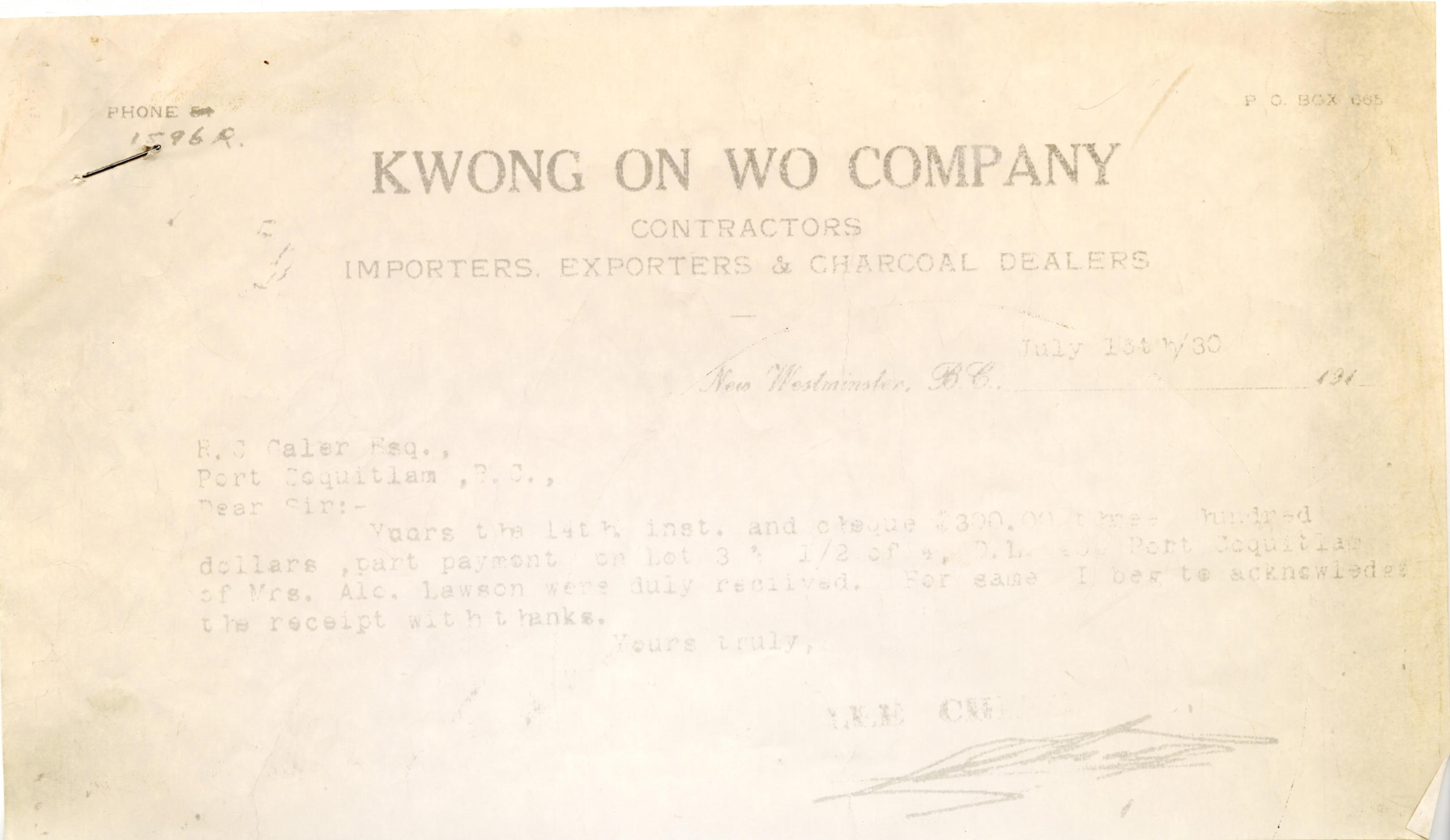

A receipt for the sale of land where the PoCo charcoal burners stood, operated by the Kwong On Wo company.

To learn more about this collection of glassware, we began by searching our own archives. Land receipts and donation records led us to a charcoal burners – a local business here in PoCo that produced charcoal in the early 1900s. The burners were owned by the Kwong On Wo Company, an important Vancouver-based company who was one of the firms responsible for supplying the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) with Chinese workers. In addition to contract labour, however, they provided charcoal for cookstoves and heat stoves aboard CPR trains.

After the charcoal burners closed in the 1920s, the buildings, including a bunkhouse for the workers, three kilns, and several wells, were abandoned. Most of the furniture and other valuables were looted from the abandoned buildings, apparently by a “laid back bachelor who needed things for his house”. What pieces of pottery and glassware remained in the bunkhouses were collected or buried by later owners. Some of these bottles are those in our collection today!

A wine bottle recovered from the bunkhouses of the PoCo charcoal burners. Embossed with the Chinese characters for “Wing Lee Wai”.

Wing Lee Wai’s Instagram account. They still operate out of Hong Kong today!

Further research into one of these bottles tells an interesting story. This wine bottle is embossed with the characters for Wing Lee Wai (永利威), meaning “Forever Well Strong”. It also has the characters for Hong Kong (香港) and Tian Jing (天津), a city in China. Founded in 1876 by Wong Sing-hui, Wing Lee Wai was once one of the largest wine distilleries in China. Popular internationally well into the 1950s, it is one of the oldest businesses still operating in Hong Kong today. They even have an Instagram account where they share pictures of their wine!

Dewdney Trunk Rd., c.1910s. “Star Laundry” was one of the early Chinese-owned businesses in Port Coquitlam.

While researching the charcoal burners, however, we discovered that they were not the only local Chinese business at this time. In fact, the earliest record of Chinese presence in PoCo goes back much further. In 1853, Captain Alexander McLean settled with his family in Port Coquitlam. They became the first white settlers in the area. Many years later, Captain McLean’s son, also named Alexander, was interviewed about his life by Vancouver’s first archivist James Skitt Matthews.

Matthews took many notes that we can still read today. Reading this interview in the Vancouver Archives, we came across an interesting comment. McLean apparently said something to the effect that Chinese people were living in Port Coquitlam even before his family arrived! Sadly he talked too fast for Matthews to write the information down and then died shortly after the interview. Nothing more was done to investigate or preserve these early Chinese stories. As a result, little is known about this community today.

As the city of Port Coquitlam continued to grow, however, so did the local Chinese community. In searching our files, we came across an interview with Gordon Lee, conducted as research for a local history book. Born in Port Coquitlam in 1917, his father worked for the CPR clearing the road into Colony Farm. From Gordon’s account, we learned that the Lee family was at the heart of local business by the early 1910s. They owned many properties downtown, including the Coquitlam Café. They also rented out land along Dewdney Trunk Road to other merchants, such as the doctor’s office and barbershop.

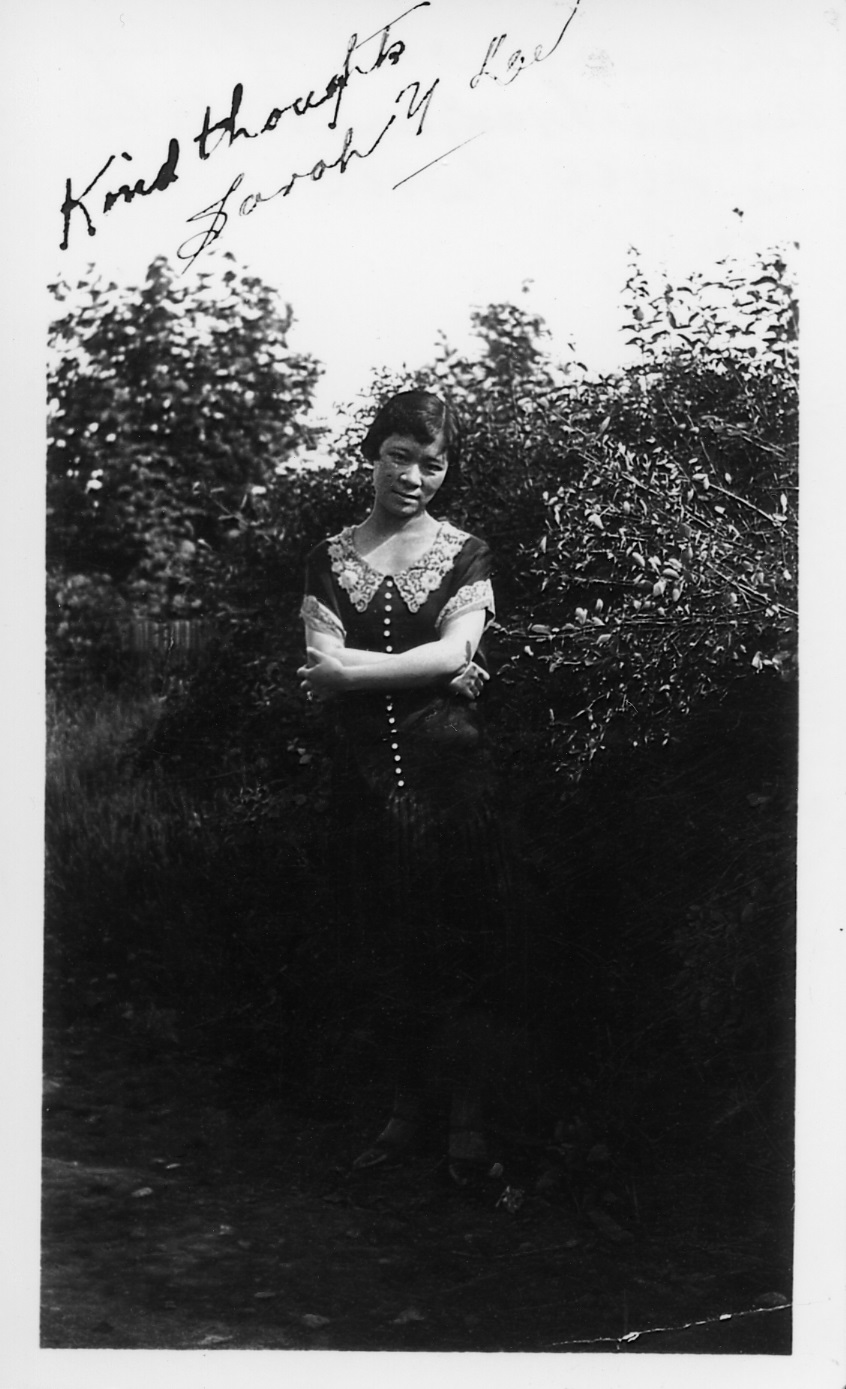

Sarah Lee, who helped run the Lee family restaurant alongside her brother Gordon.

Without Gordon Lee’s interview, much of this information may have been lost to time. Imagine how much we might know if more members of this early Chinese community had been interviewed! The history and heritage of our city is diverse. From the documents and artifacts we collect to the community members who help us interpret it, how we preserve, understand, and communicate heritage must reflect this.

Thank you to:

Queena Li

Cynthia MacMillan

Mallorie Francis

Alex Code

Aynsley Wong

Lily Liu

Pippa Van Velzen

Bryan Ness

Wongs’ Benevolent Association